How Thrilling

How does context, technology and Michael Jackson change our performance?

Elements from Michael Jackson‘s “Thriller” — the icon, the choreography, the zombies — establish different contexts in different spaces prompting people to dance. The installation was staged three times, using the same spaces but in different combination to explore how context and technology shape our everyday performance.

Michael Jackson’s Thriller is the continuous prompt. Someone might not know Thriller, but maybe they know Beat It or Billie Jean; or the moonwalk or his gravity-defying lean. It’s this familiarity that gets people engaged, and once engaged, the familiar is switched.

Role: concept, research, design, development

Tools: Node.js, PeerJS, Kinect, Michael Jackson

The Switch

In the installation, bodies are technologically identified and extended from one context to another. In different ways, the contexts are suddenly changed to underline how we identify ourselves, are identified by others, and how technology identifies us.

Staging One: Context Sets Expectation

The Hint

In the first staging, MJ’s thriller plays silently on loop, setting an expectation for the subsequent scenes.

The Audience

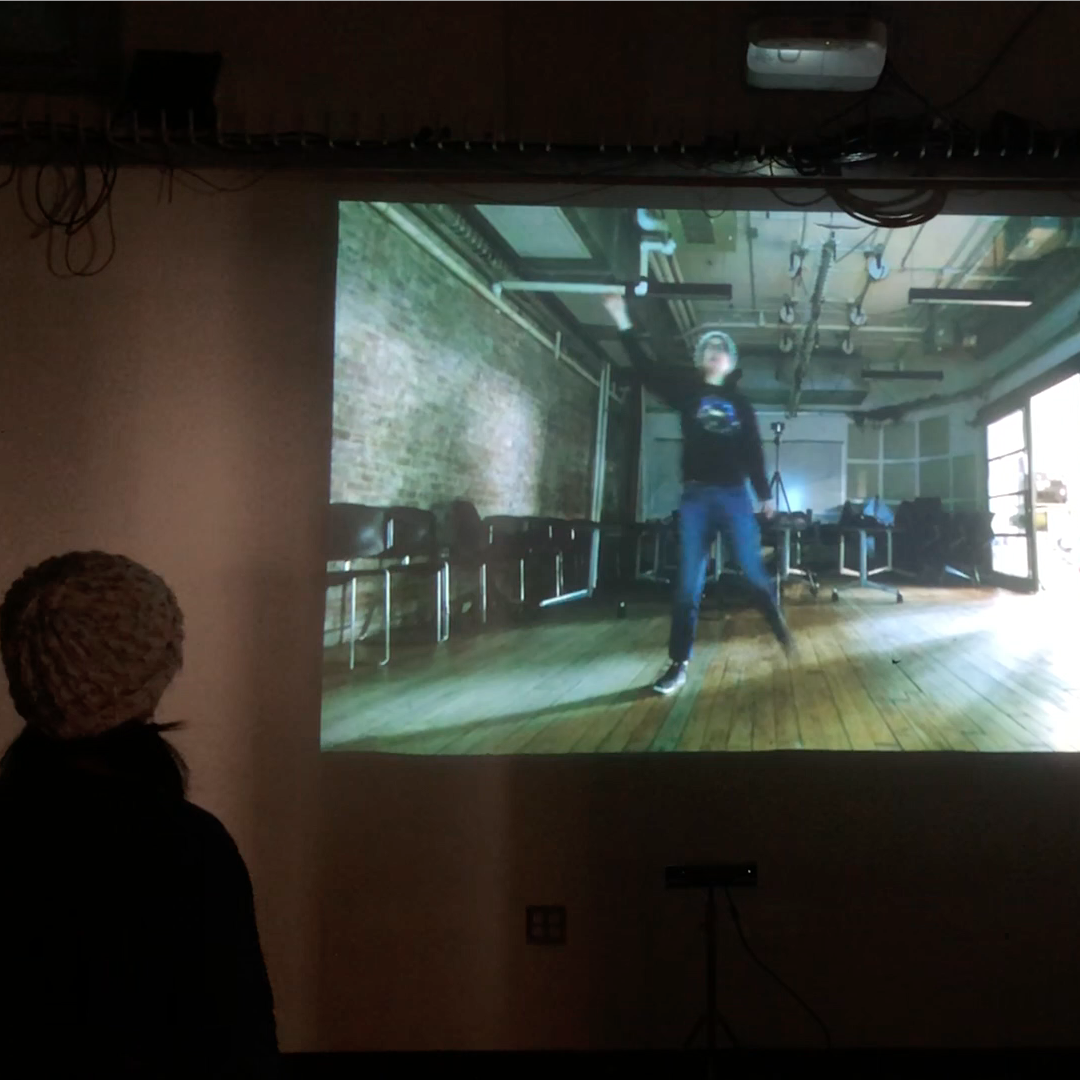

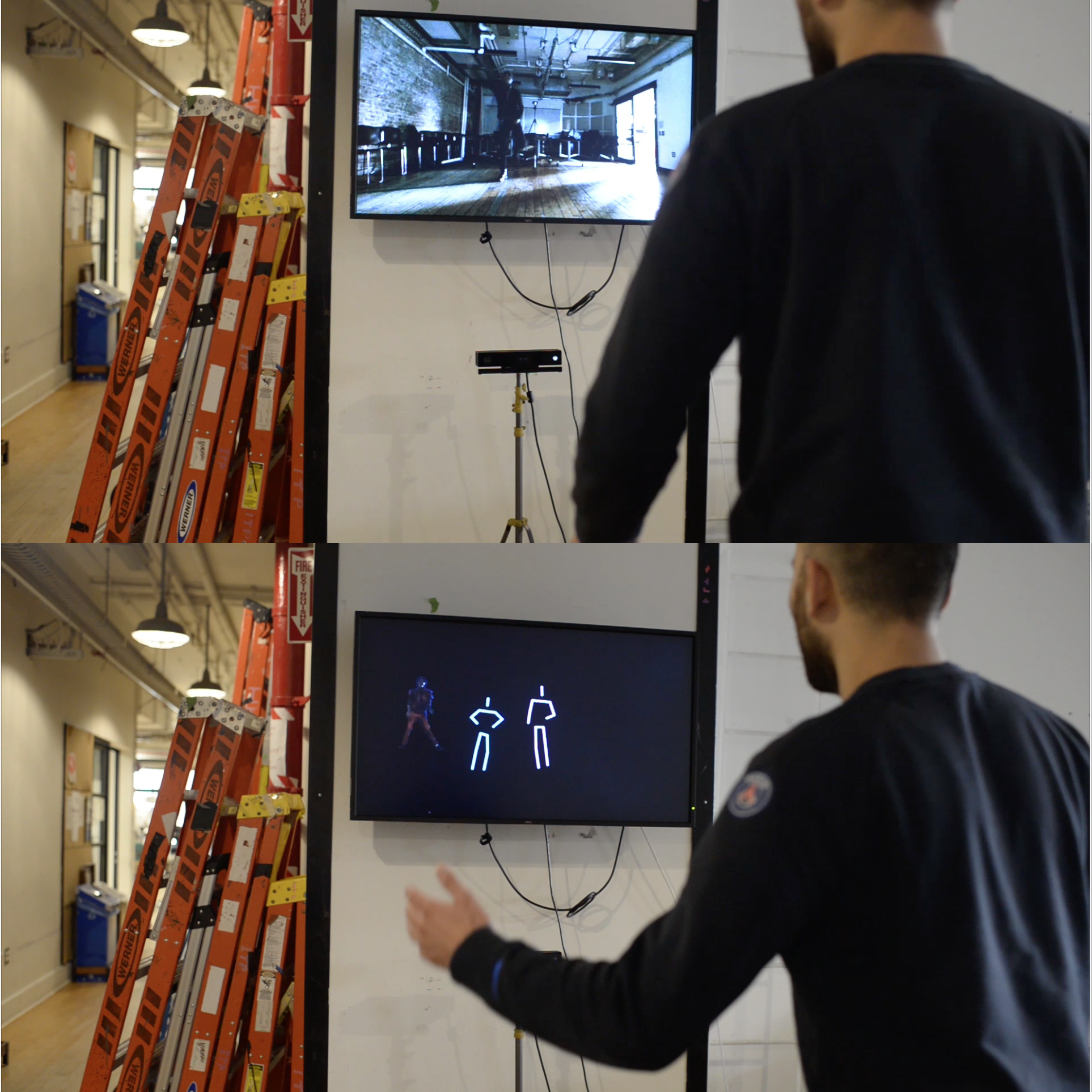

Around the corner, an audience watches a live stream of someone dancing to Thriller.

The Performance

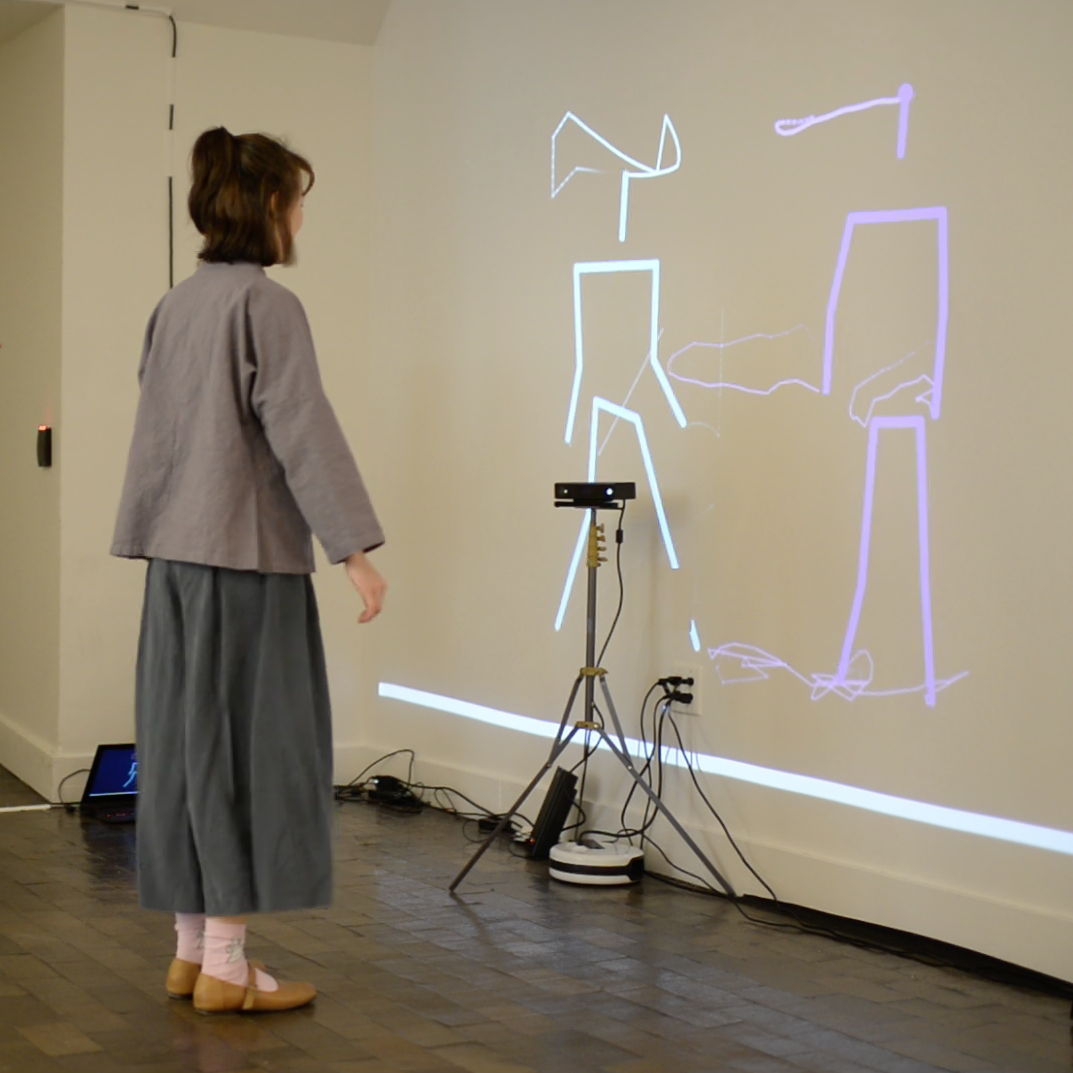

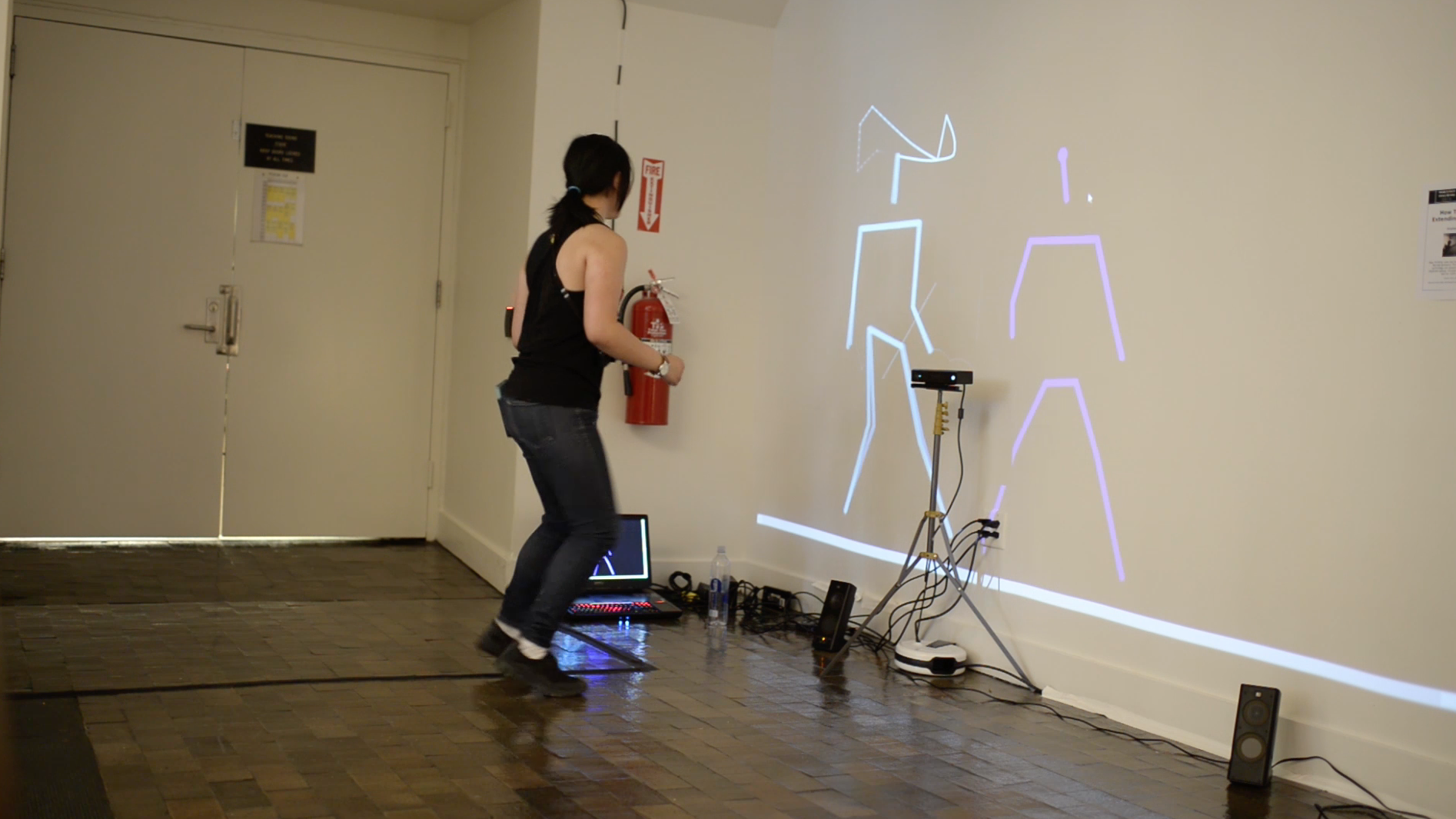

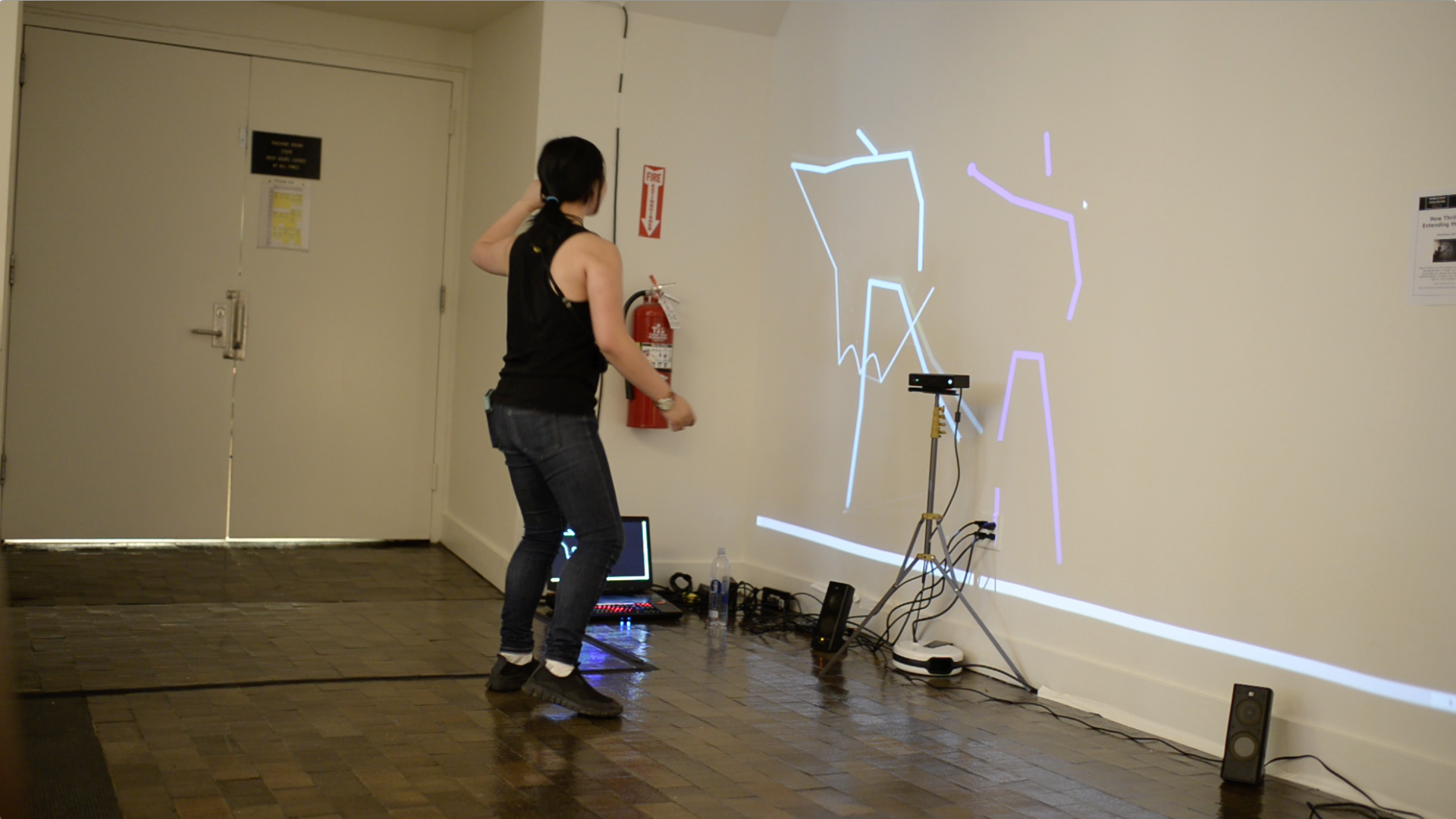

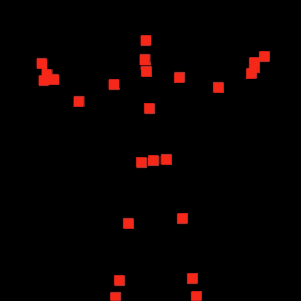

The dancer is elsewhere, detected and represented as a stick figure, along with Michael Jackson, looping and prompting us to dance.

The Switch

The dancer’s feed is suddenly replaces with a video feed of the audience watching elsewhere.

Staging One

The first staging establishes an expectation to dance. When one context switches, the performance changes as we try to make sense of the new situation. We stop dancing. We try to determine if the feed is live or recorded. Knowing about the other side, we abandon Michael Jackson and make up a new routine.

Staging Two: Extending the Body

The Original

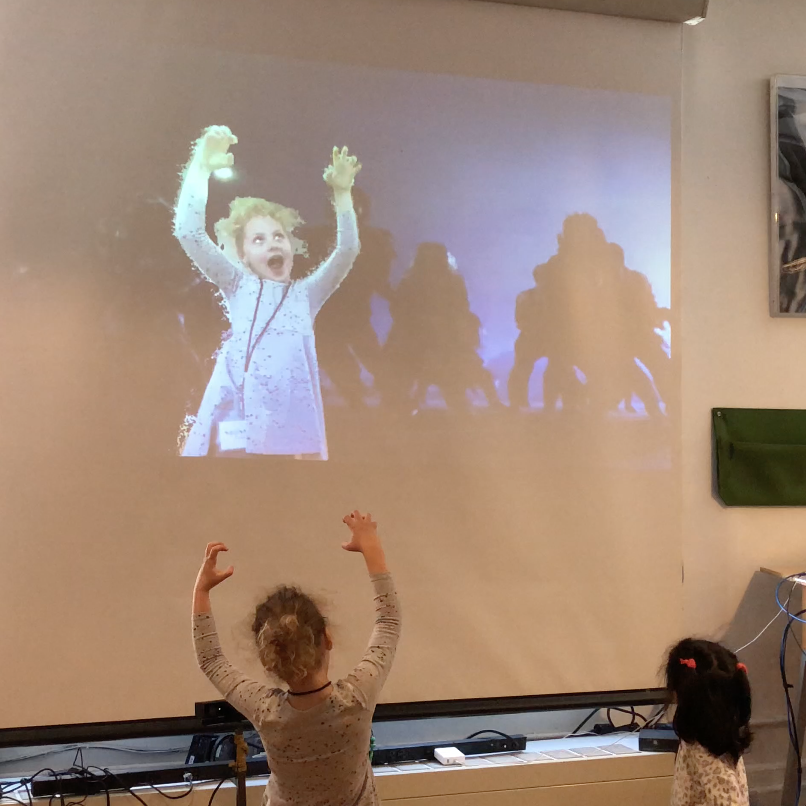

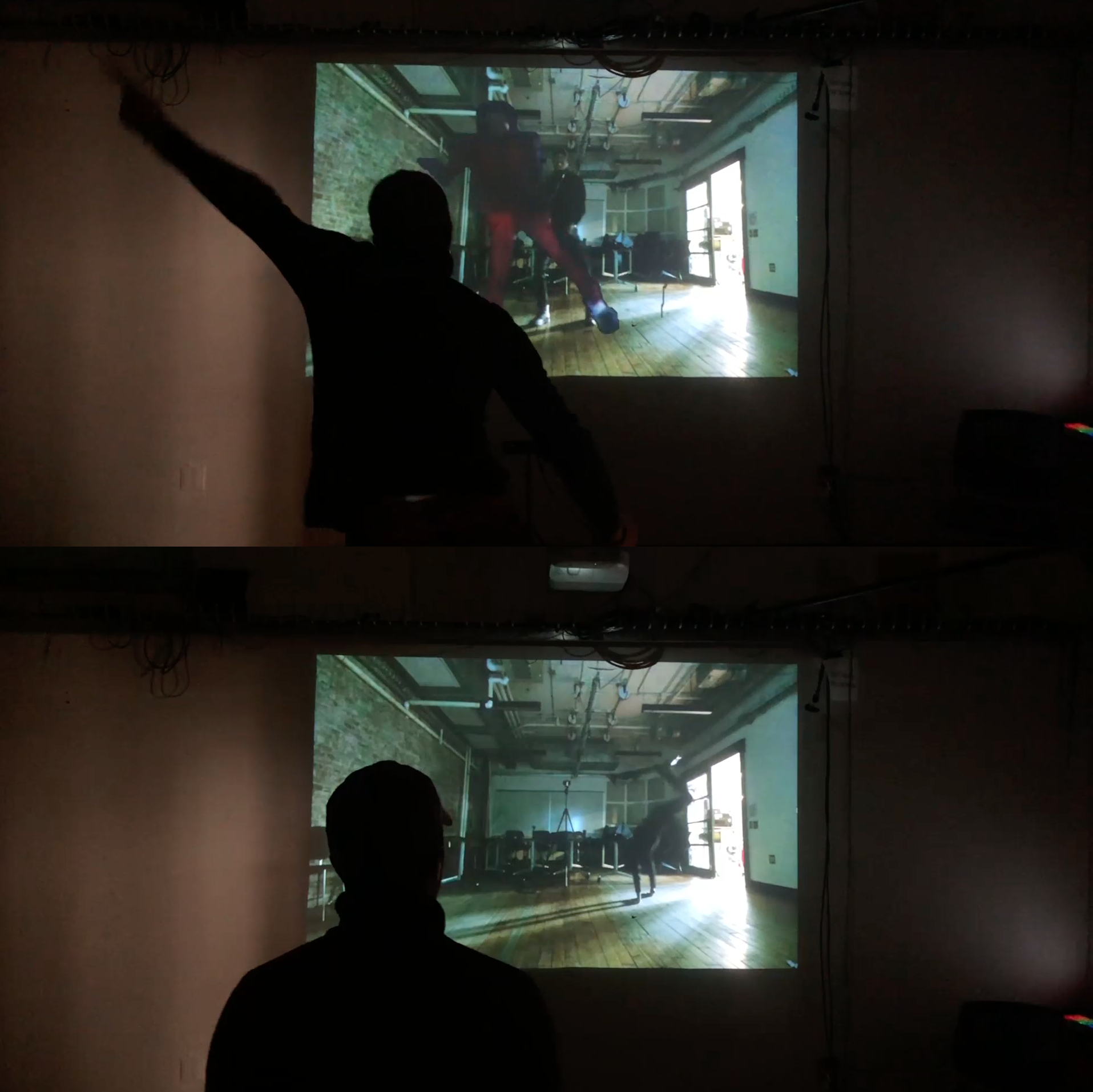

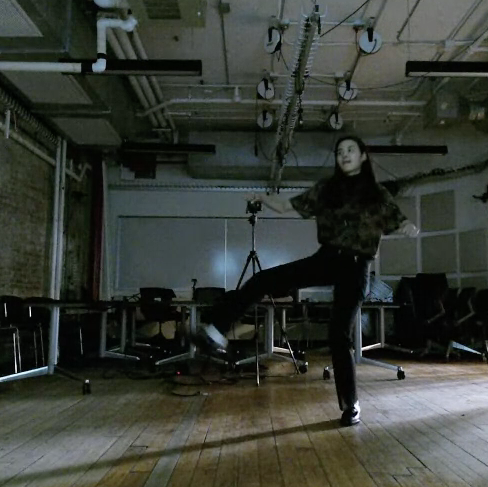

In a dark room, someone is detected and sees themselves in a clip from the original thriller video, prompting them to dance.

The Partner

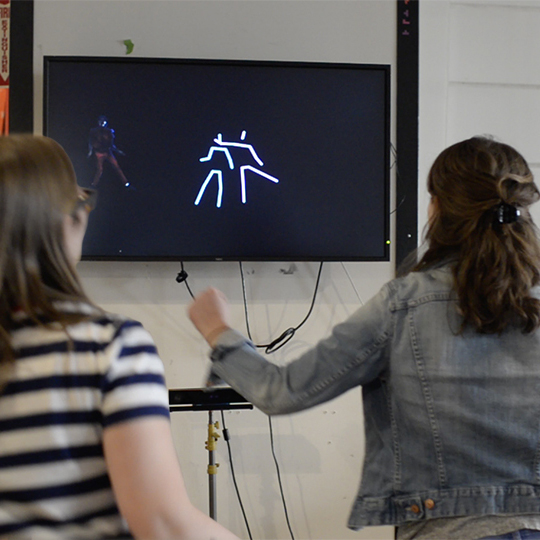

Elsewhere, the first dancer is shown as a cutout, prompting others to dance. Someone in the audience is detected and sees themselves as a stick figure.

The Flicker

In the first room, the video flickers to reveal a live stream of their dance partner and audience elsewhere.

The Recording

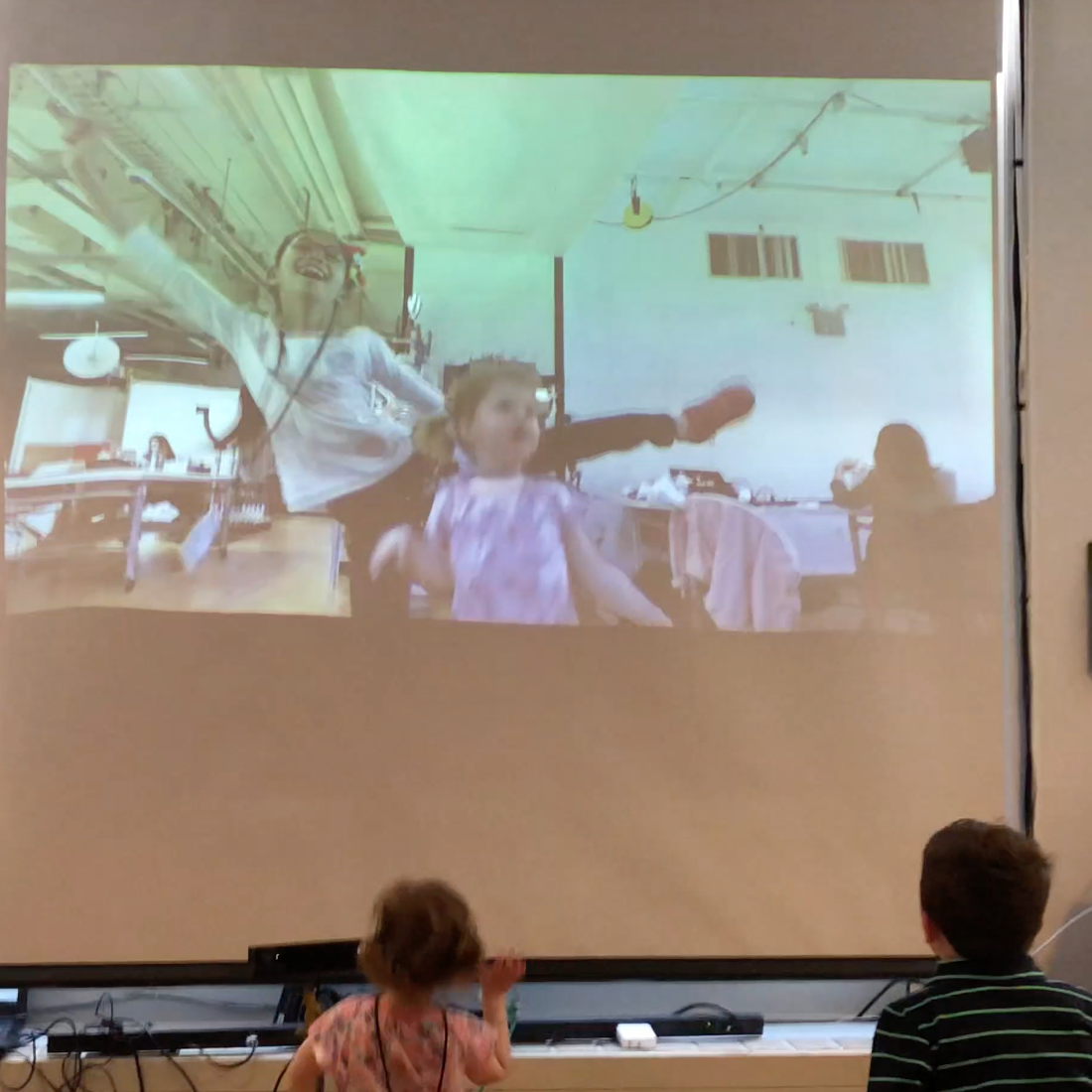

Later, in the hallway, the first dancer becomes an audience to themselves. A recording of their dance is juxtaposed against Michael Jackson.

Staging Two

In this staging, a single performance takes on different meanings in different spaces. First we’re a zombie when identified by technology. Second, we’re a dance partner when identified by an audience. Finally, we’re a point of comparison to Michael Jackson when identified by ourselves.

Staging Three: Performer and Audience

The Lesson

Someone sees themselves and Michael Jackson in a mirrored video feed of their own space. Music playing and Michael Jackson dancing prompt us to dance

The Playback

Michael Jackson disappears and the dancer watches a playback of themselves.

Just Watching

Elsewhere an audience watches a silent live-stream of the dancer.

Now Performing

The video feed of the solo dancer suddenly disappears. The audience is detected and each sees themselves as a stick figure. A cut out of Michael Jackson dancing prompts them to dance.

Staging Three

There are two switches, each in their own space. First, someone dances with Michael Jackson, then becomes an audience to their own performance without him. Elsewhere, this solo show is a hook for people to gather, turning the unwitting audience into collective performers. Our role changes with a change in context and how we’re identified by technology. We go from performer to observer, audience to dancer.

Conclusion

As technology enables us to extend ourselves, it also acts to identify. We’re seen in a space, isolated as a cut out, abstracted as dots. And so we negotiate our identification with ourselves, those around us, but also with the standards encoded within a technology.

The kinect camera identifies you as a person because you perform how it expects a person to perform. But it also might not recognize you because our performance or bodies don’t match the standards codified within the device. Each performance is a negotiation of how we identify ourselves, how we’re identified by others, and how technology identifies us. And hopefully by people participating in them, this question is drawn a bit more to the fore.